Ecuador: Ecuador is striving to re-establish ties with the International Monetary Fund and World Bank,

2014/09/14

Ecuador is striving to re-establish ties with the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, tap international capital markets and embrace orthodox economic policies. However, when it comes to banking, the country's new direction is not proving to be universally popular.

Until recently, Ecuador’s president, Rafael Correa, had tense relations with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), often lambasting the institutions in public. However, there are signs that this attitude is thawing.

Not only that, but Mr Correa is also turning to orthodox economic policies as he tries to tap more sources of finance to sustain an ambitious investment programme in the country. This has led to the World Bank agreeing to extend $1bn in total credit to Ecuador and the IMF resuming its annual reviews of the country's economy.

These improvements have paved the way for a more dramatic U-turn. On June 17, Ecuador sold $2bn-worth of 10-year sovereign bonds in New York, making a successful return to international capital markets. Joe Kogan, emerging markets director at Scotia Capital in the US, says that this step “is that much more impressive” considering that it was only in 2008 when Ecuador defaulted on $3.2bn of its external debt, or about one-third of the total, citing reasons that sounded “very strange to the New York investment banking community” by arguing that the debt was “illegal and illegitimate”.

“There was no question of ability to pay, due to an economic crisis or shock. It was entirely [about] willingness to pay,” says Mr Kogan.

Not only was the June bond issue successful, it was hugely oversubscribed. Ecuador’s finance ministry says demand was in excess of $5bn. And although the bonds were priced at 7.95%, which is more than what some other Latin American countries pay to borrow, the rate was less compared with Ecuador’s previous dollar-denominated bond issue in December 2005, when the price was 10.75%.

Low-leveraged economy

Nathalie Cely, Ecuador’s ambassador to the US, believes that one of the reasons why the issue was so successful is because the ratio of Ecuador’s debt to gross domestic product (GDP) was very low after the 2008 global financial crisis and, even after the recent borrowing, it is still only 22.1%, at the low end in South America. “Ecuador is a low-leveraged economy in every sense,” she says.

Data from Ecuador's ministry of finance and banking regulator shows total credits by privately owned banks in Ecuador amounted to $23.6bn in the year to the end of March 2014, equivalent to about 33% of the country’s estimated $72.5bn GDP in 2013. Additionally, Ecuador’s economic growth over the past seven years has averaged 4.2% annually, well above the 3.5% regional annual average, and the country is also deemed to have sound macroeconomic rules and regulations. It is a constitutional norm, for example, that government expenditure can only be financed by stable revenue streams, such as taxes and oil revenues. The output of oil continues to be fundamental to the Ecuadorian economy, accounting for one-third of taxes and half of exports.

“It was [also] the right time to do [the issue],” says Ms Cely, in agreement with New York analysts who emphasise that there is big investor demand for higher yielding emerging market debt as long as interest rates are low in the US, the EU and Japan.

However, an essential condition for the sale was that Ecuador reach an agreement with holdout creditors of the defaulted bonds – those who refused to accept Ecuador’s offer when the country bought back about 93% of the $3.2bn debt in 2009 at a mere $0.35 to the dollar.

Meanwhile, in the same month as the government borrowed $2bn in bonds, it also obtained a $400m loan from Goldman Sachs, pledging some of Ecuador’s gold reserves as collateral.

Search for alternatives

It is not hard to find the reasons why the Ecuadorian government is stepping up its search for alternative sources of finance. Oil revenues in the country have been doing well, with both production (crude oil production is at 526,000 barrels of oil per day according to the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) and prices going up. And thanks to more efficient tax collection, tax revenues have doubled since 2008. At the same time, the government has also been spending a lot to transform the public sector, develop infrastructure and improve living standards.

Official data show that between 2007, when Mr Correa first took office, and the end of 2013, public investment amounted to $36bn, compared with a meagre $6bn invested between 1998 and 2006. This year the government’s planned public investment is $7.36bn.

The government has increased spending at all levels of education, healthcare, roads and environmental protection, as well as expanding the oil frontier in the southern Amazon and allowing large-scale mining. But projects it considers transformational, notably the final phases of several hydroelectric power plants and a $12.5bn Pacific coast oil refinery, need more funding.

China’s credit

Ecuador has depended heavily on China for finance in recent years. Government officials say China has lent Ecuador $11bn since the 2008 default, with part of this credit backed by pre-sales of crude oil.

The upshot is that deficits have actually been increasing. Last year the Ecuadorian government’s budget deficit was $5.4bn, 5.5% of GDP, according to the central bank. This year, the ministry of finance forecasts a $4.94bn budget deficit.

On top of this, since 2000, when Ecuador took the radical step of adopting the US dollar as its official currency following a devastating banking and economic crisis, the central bank no longer has the capacity to print money, devalue or act as lender of last resort.

Referring to Ecuador’s return to international markets, Mr Kogan says: “The country has a dollar economy. So, in order to continue its current policies [of public investment maintaining economic growth], it needed some access to finance.”

The return will also make certain types of banking transactions easier, according to Mr Kogan. “Theoretically, trade finance becomes easier and also longer term lending. Once the sovereign can borrow, corporates can borrow. The sovereign establishes a benchmark,” he says.

New legislation

Against this background, after the positive signs of a successful return to capital markets and improved relations with international financial institutions, the introduction of the financial and monetary code passed by the National Assembly in July is a disappointment to the private sector, according to some analysts and bankers.

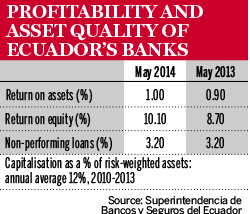

Profitability and asset quality of Ecuador banks

“Bankers are very upset by the new legislation. They consider it a backward step,” says Ramiro Crespo, a former banker at Citi who is now president of Ecuadorian investment firm Analytica Securities.

But Patricio Rivera, Ecuador’s minister for economic policy, in presenting the legislation to parliament said it is consistent with the president’s new political and economic model of putting citizens in charge, not banks and capital. He added that the regulations are necessary to create jobs, support economic growth and redistribute wealth. Another objective of the code, he said, is preventing a re-run of Ecuador’s dire banking crisis of 1998-99.

To achieve these aims, the law expands banking supervision and establishes higher minimum bank capital requirements, as well as limits on external borrowing and limits and conditions on the holding of foreign assets by banks.

Severe penalties are also introduced for banks that break the new rules, including substantial fines, the removal of directors and the revocation of licences. That the sovereign will not be liable for the solvency of the private financial sector is spelt out; in other words: there will be no more state bailouts.

Ms Cely at Ecuador’s embassy in Washington says an innovation of the code, which takes effect later this year, is that it centralises the regulation of all financial sectors, including banks, insurance companies, brokerages and the stock exchange, into a single board of monetary and financial regulation.

She adds: “Of course you need regulators who have expertise in a particular area or niche. But nowadays, [with a] compartmentalised approach, it is very difficult to have a systemic view. You need to see the whole picture, have better information, better warning systems. So personally I like the way we are introducing one-stop financial regulation.”

Ecuadorian banks at a glance

According to Ecuador’s superintendency of banks, the country’s four largest institutions: Banco del Pichincha, which had the biggest profits in 2013 ($53m), followed by the state-owned Banco del Pacífico ($41m), Banco Guayaquil ($40m) and Produbanco ($29m), own 63% of the banking system’s total assets.

Foreign-owned banks include Citigroup of the US (which has a large remittances operation), the Dutch-German Procredit (which is the country’s leading microcredit bank) and Panama’s Promerica.

In the 12 months to the end of March this year, privately owned bank loans amounted to $23.6bn, 12.2% more than the previous 12 months. The breakdown was as follows: 62% commercial loans, 25% consumer credits, 10% microcredits and 2% mortgages.

Balance of power

But Ecuadorian bankers say the new board, made up entirely of government ministers, concentrates too much power in the hands of the government. César Robalino, executive director of the Association of Private Banks of Ecuador, says one aspect of the new rules that particularly concerns bankers is to what extent, and in what way, the board may direct and allocate bank credit.

It is no secret that the government wants credit to be directed more towards what it calls productive sectors, such as agriculture and small businesses, as well as the priority areas of higher education, tourism, biotechnology and some agribusiness. The aim is to try to reduce Ecuador’s dependency on natural resources, particularly oil.

But Ecuadorian officials are set in their opinion. Ms Cely says: “There is nothing in the new code and there is not going to be anything like the government telling a bank that it has to lend a certain percentage of its credit to developing water infrastructure, for example, and it has to lend at 9% and for 20 years. That would be like the credit of a public bank, [which is subsidised]. We already have that.” In fact, according to the ministry of finance, the credit of state-owned banks amounted to $21bn between 2007 and 2013, seven times more than between 2000 and 2006.

Promoting diversification

Nonetheless, officials say that the new code will introduce tax and other incentives to promote financial instruments, such as venture capital funds, which do not presently exist in Ecuador. It will also prioritise lending in certain sectors and markets to promote a more diversified economy. And there will be disincentives for lending to sectors that do not fit in with the government’s programme.

Consequently, Mr Robalino says, bankers think consumer credits, such as credit card loans, car loans and credits to buy household appliances, “will be punished in the new system”. That, he says, would be a further blow to bank profits as these credits have higher interest rates than business loans or other types of lending that the government calls “productive” according to existing central bank rules on interest rate caps on credit.

Indeed, Mr Robalino believes that the unintended consequences of the new legislation could be banks having lower profits and a decline in the amount, and possibly the quality, of credit.

Banker concern

Bankers are also deeply concerned about the new regulatory board taking control of a reserve fund – which Ecuador’s private banks established after the dollarisation of the economy – to serve as a rescue fund should a single bank get into difficulties, as opposed to a systemic financial crisis.

Ecuadorian officials say the disagreement here is basically ideological: about whether self-regulation by banks is considered preferable to external and independent regulation for the banking system.

Mr Robalino says currently the reserve fund, which is financed by bank shareholders and bank deposits, has about $2.5bn in resources, much of it invested in short-term paper issued by the Bank for International Settlements and Fondo Latinoamericano de Reservas, both with triple AAA credit ratings. In contrast, if this money had to be invested in Ecuador, in central bank debt, for instance, this has much lower credit ratings but a higher yield.

“The issue of liquidity in relation to the new code is enormously problematic and delicate for the banks,” says Mr Robalino.

Mr Crespo at Analytica Securities goes further, raising doubts about the sustainability of the government’s economic model as a whole. “Ecuador is growing well because of oil prices, because of borrowing. But there is concern about how long this can last. The limit is that you cannot rely on the state, on the government doing the tasks that the private sector can do better,” he says. “I think what the government has to do is make the country more attractive to private investors.”

- Related Articles

Climate change laws around the world

2017/05/14 There has been a 20-fold increase in the number of global climate change laws since 1997, according to the most comprehensive database of relevant policy and legislation. The database, produced by the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and the Sabin Center on Climate Change Law, includes more than 1,200 relevant policies across 164 countries, which account for 95% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Presidencia Perú

2017/03/04 The PPK cabinet has been working diligently to modernize the country and replace business confidence, while unlocking investments and infrastructure megaprojects in a bid to boost the country’s economyGuayaquil is going to be a major conference and convention hub

2016/01/16 Guayaquil is a city with a purpose, and that is to make sure its visitors have a good time. One of Ecuador’s most versatile destinations has polished its tourism act, presenting today’s visitors with a multi-tiered offering

Ecuador Outlook for 2013-17

2013/10/31 The country (Ecuador) is situated in Western South America, bordering the Pacific Ocean at the Equator, between Colombia and Peru. It has borders with Colombia for 590km and Peru for 1420km. Land in Ecuador is coastal plain (costa), inter-Andean central highlands (sierra), and flat to rolling eastern jungle (oriente). OVERVIEW The continuation of the improved political stability that Ecuador has enjoyed in recent years since Rafael Correa became president, although conflicts over environmental issues will sustain the risk of social unrest. The president remains highly popular, and his commanding majority in the National Assembly (Ecuador's Congress) will relieve the passage of legislation.

- Ecuador News

-

- ISRAEL: Netanyahu’s Historic Latin American Tour to Highlight Israeli Tech Sector

- ISRAEL: PM Netanyahu leaves on historic visit to Latin America

- AFGHANISTAN: UNWTO: International tourism – strongest half-year results since 2010

- AFGHANISTAN: Higher earning Why a university degree is worth more in some countries than others

- ARGENTINA: China looks to deepen ties with Latin America

- ECUADOR: Guayaquil real estate Big construction projects to substantially improve quality of life

- Trending Articles

-

- SOUTH AFRICA: Nigeria and South Africa emerge from recession

- BAHRAIN: Bahrain issues new rules to encourage fintech growth

- UZBEKISTAN: Former deputy PM named Uzbekistan Airways head

- ARUBA: Director of Tourism Turks and Caicos after Irma: Tourism, visitors, hotels current status

- AUSTRALIA: Western Australia joins two-thirds of country to ban fracking

- ANGOLA: Angola: Elections / 2017 - Provisional Data Point Out Qualified Majority for MPLA